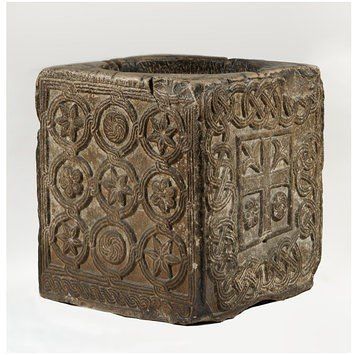

Marble well-head. Made in Murano, Italy during the 9th century, the artist and

maker are unknown. It is kept in the V&A

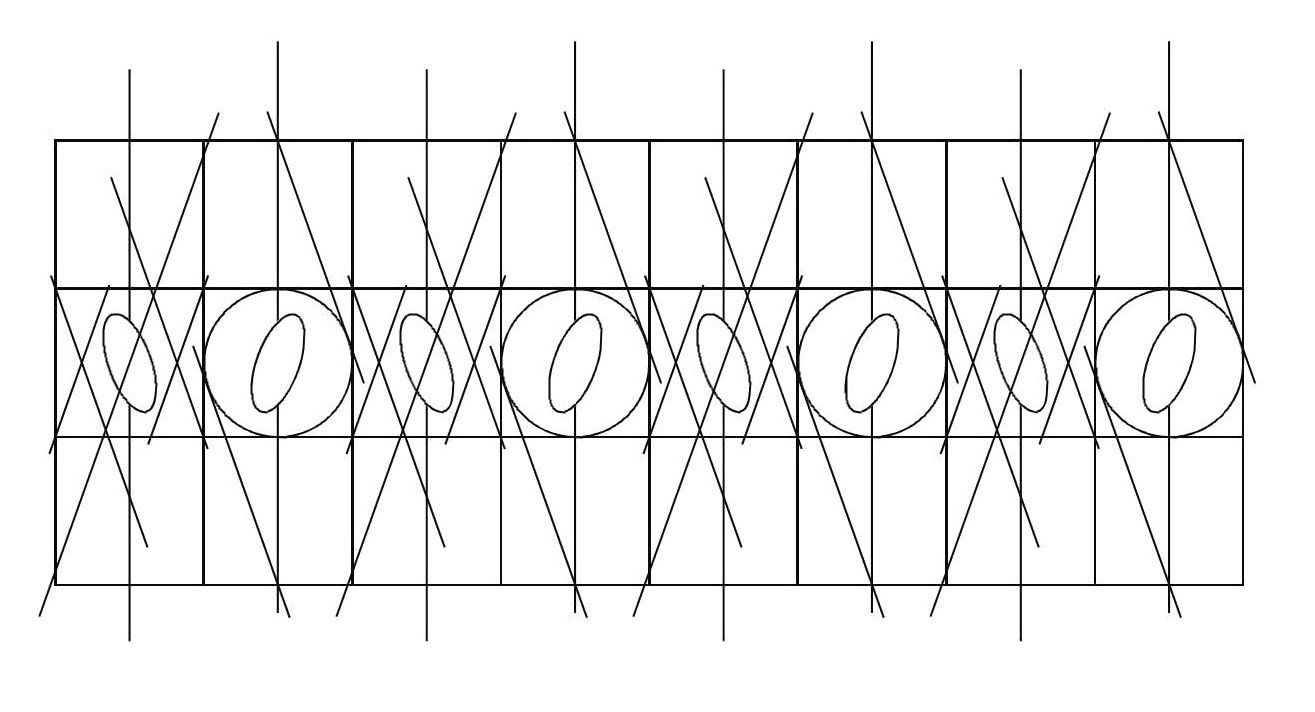

Lump

: square silver bangle

Not a lot of solderin'... but a deal of 'ammerin' and sawin'.

As we know them today, well-heads have a very different function from their medieval counterparts. Now, they are an integral part of the installation of oil and gas wells, are entirely functional and if they betray any decorative merit, it is in the brutal tangle of their associated pipe-work.

Before developing into the bespoke artefacts they eventually became, the earliest well-heads were constructed by using 'found' and/or leftover objects. Over time they were deliberately 'made' and whilst the decoration of their exposed surfaces might be construed to be of secondary importance, the designs carved into them mirrored the community's religious and secular and concerns. They betray a proximity of form and design, affording a glimpse into the society which had it’s being about them.

As one walks down the entrance steps of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Well-head (54-1882) stands sentinel over the other objects displayed there. Without its life-preserving function one might imagine many of the other artefacts that share its space, not having come into being.

Comparisons routinely made between museums and churches can be odious but stepping into Room 8 does feel a little like walking through the West door of a church and 'passing through' the font before taking one's place in the nave.

This great lump of marble was formed in the first place of recrystallized matter deposited both in and by the water the well-head was designed to contain. As such the two have a symbiotic relationship.

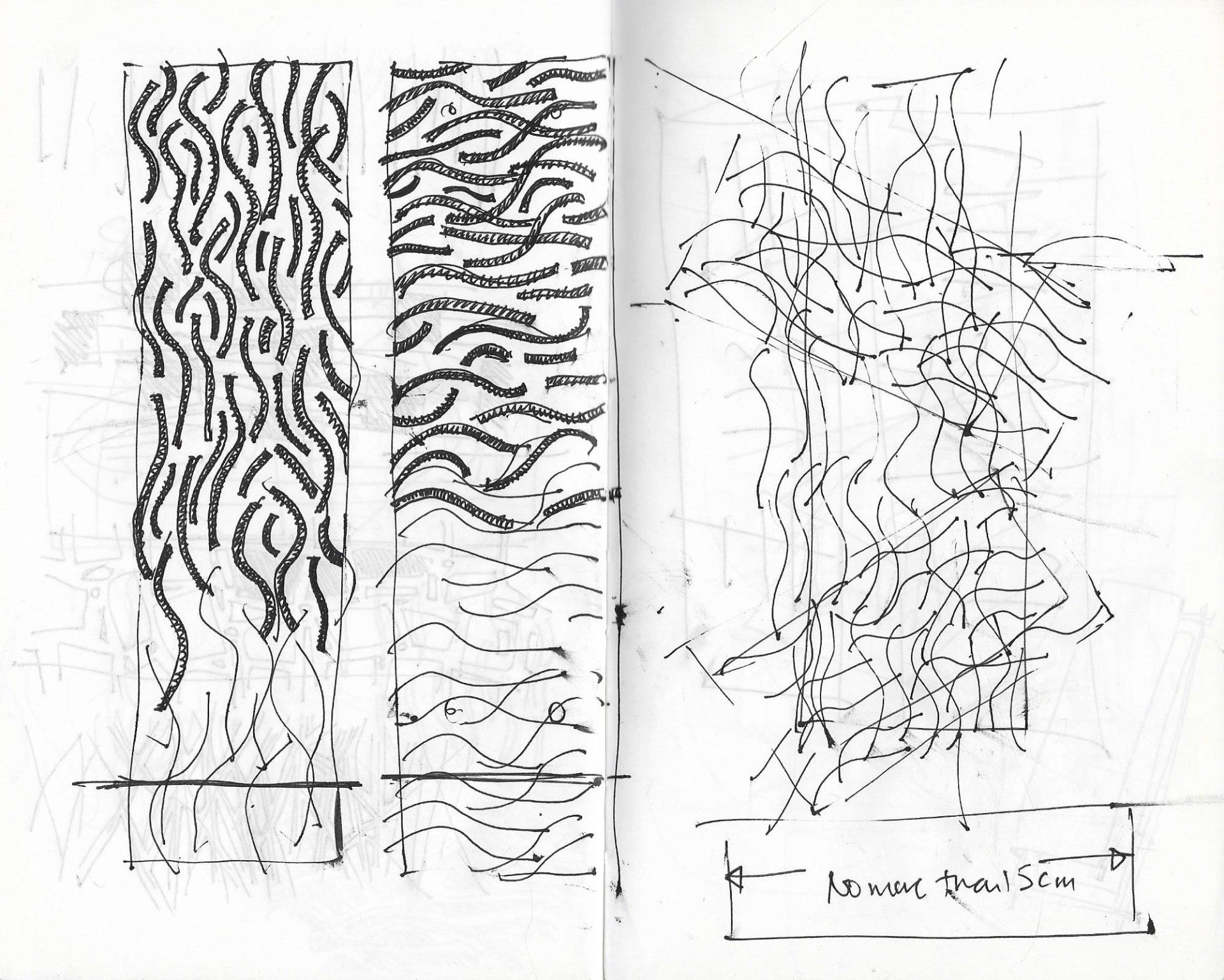

As I looked and drew I began to appreciate that the apparently simple regular decoration was anything but and thought of ways it might be re-interpreted. I wanted the finished item to betray a sense of substance, like marble, whilst at the same time giving a feeling of the aqueous-ness of water. How many lovers I wonder have sat on the edge of this well-head during the course of its working life and drawn their fingertips through the water; and how many tip-toeing children, have leant over its edge and dropped pebbles in to bring the water to life?

Fabrication seems to be morphing into reflection.

But what I wonder, are we reflecting? The world about us? Ourselves?

Our desperate need to be lauded?

A decade or so after The Beatles broke up, a bloke called Donald Schön wrote a book called The Reflective Practitioner. In it he introduced the concepts of reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action explaining how we meet the challenges of our work with a kind of improvisation that is improved through practice. The concepts underlying reflective theory are however much older, some scholars claiming to have found them in the writings of, amongst others, Marcus Aurelius.

Central to it is an interest in the integration of theory and practice, the cyclical pattern of experience and the conscious application of lessons learned from it.

When a person is experiencing something in the moment, he or she may be implicitly learning. It can though be difficult in that same moment to put emotions, events, and thoughts into a coherent sequence. When however we rethink or retell events, it is possible to categorize them (and the emotions and ideas surrounding them), and so compare the intended purpose of a past action with the results of it. Stepping back permits a critical reflection.

Is it all just pseudo-academic twaddle or does reflective theory have anything to do with what I've been making? Goodness knows.

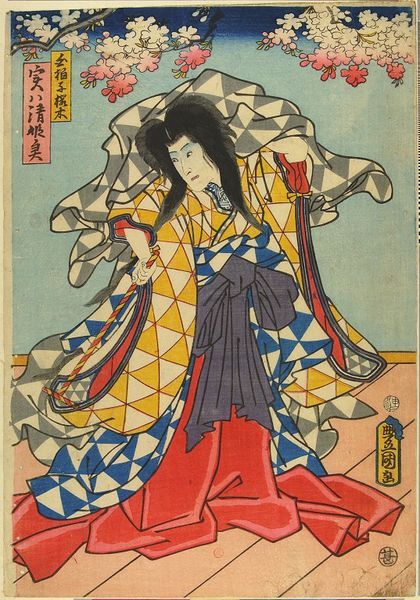

All of which led me to a woodblock print by Utugawa Kunisada I. Published in 1860 by Maruya Jinpachi.

Following the brooch, came a couple of folded-silver rings (a little more practical in the wearing)… though not entirely.

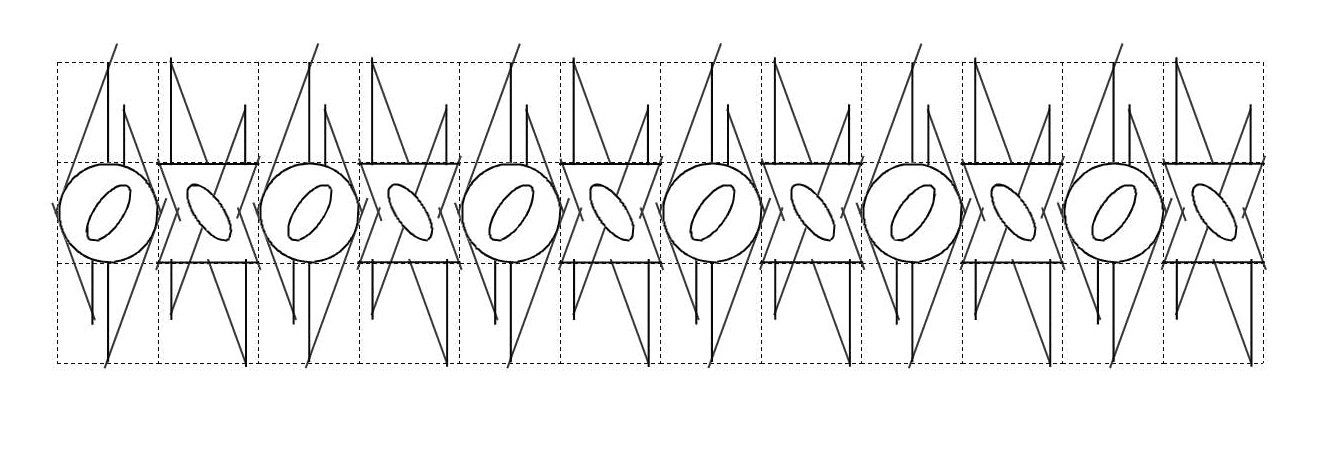

Yukata

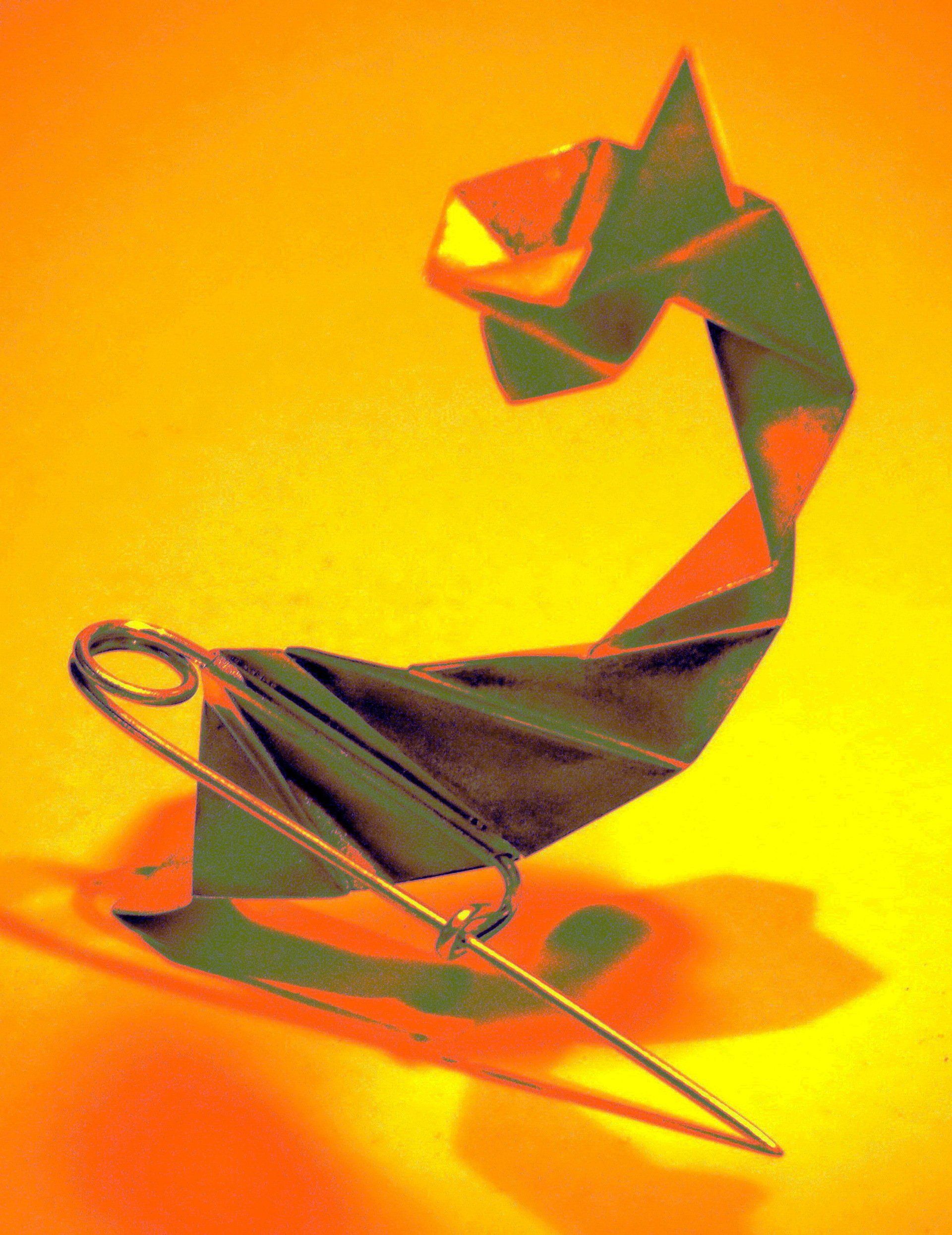

: large folded-silver brooch

Lots of schoolboy geometry, a deal of scorin' and foldin', a little bendin' and lots and lots of solderin'.

Obi

: folded silver ring #1

Disambiguate

:

folded silver ring #2

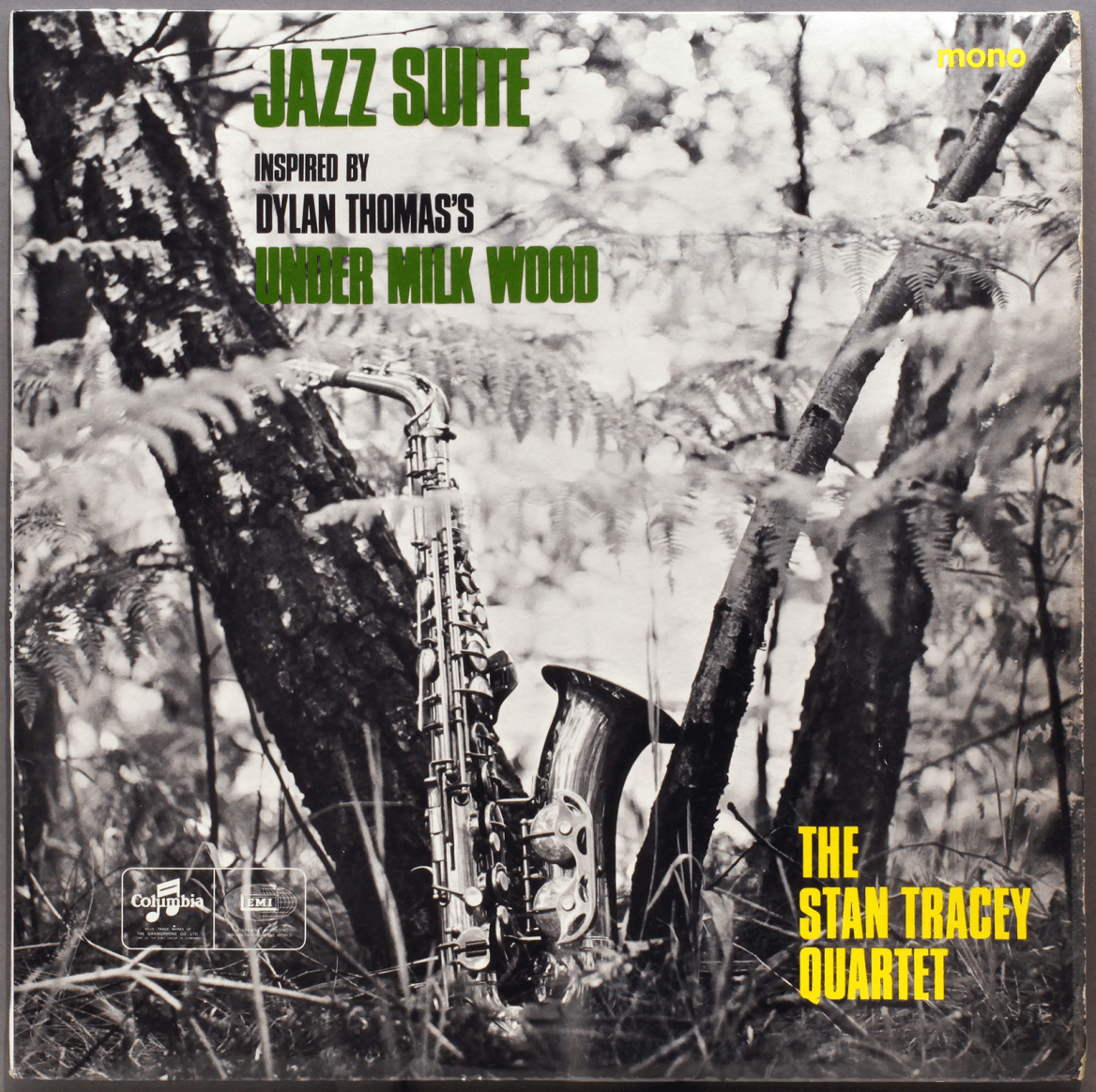

'To begin at the beginning...'

Here's one I made earlier.

'It is spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black.'

I am listening to Stan Tracey's original recording of 'Jazz Suite' inspired by 'Under Milk Wood' (on the Columbia label). It's now very hard to find a vinyl original that doesn't look like it's been kicked round a car park... but I digress.

As I listened I heard in my mind's ear Richard Burton's sonorous delineation of the text of this play for voices. Llaregyb we come to understand, is a backward place. 'Everything you can think of is true.' Tom Waits

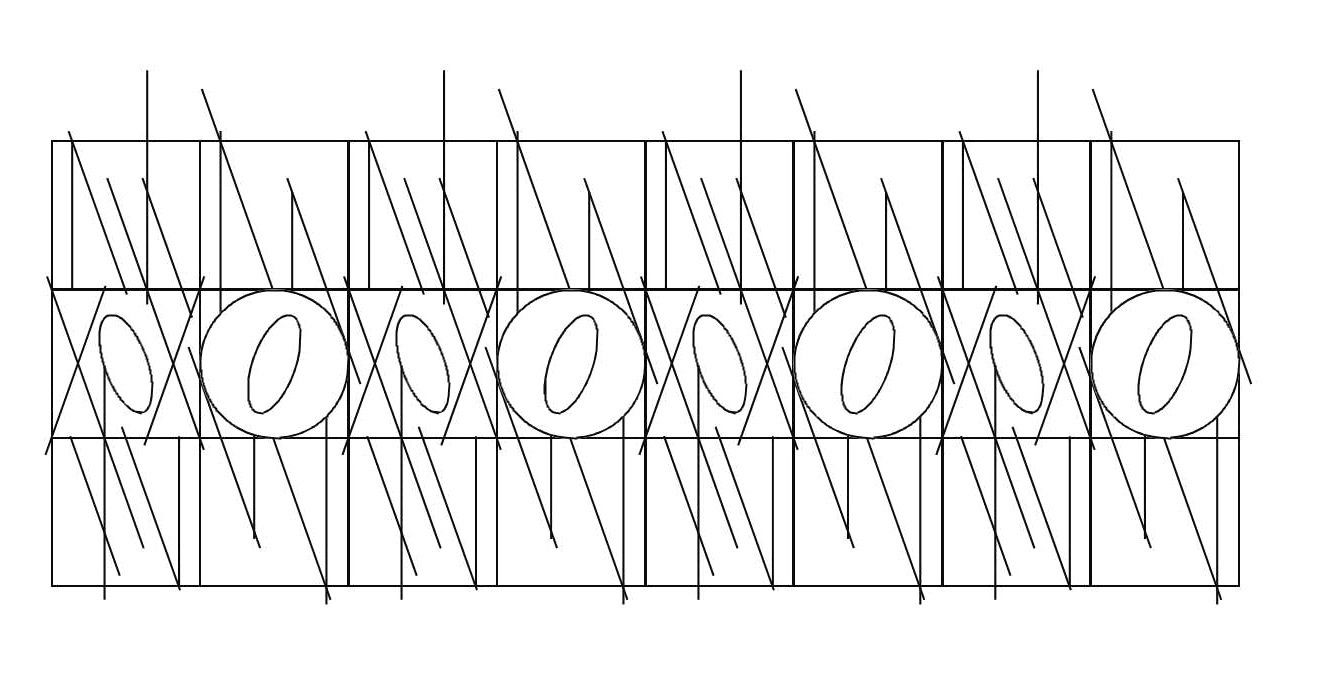

Contrary

: pierced silver bangle

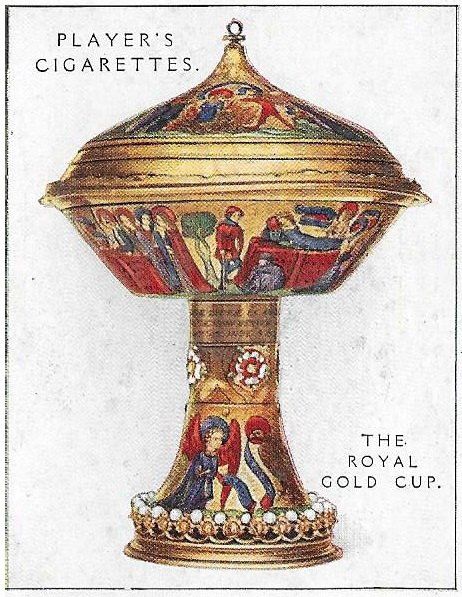

Exemplars #1 ::: The Royal Gold Cup of the Kings of France and England

This: 'remarkable specimen of goldsmith's work... belongs to a class of which but few examples are known to exist. Its interest as a historical relicis very great, both to the people of England and France, while its artistic merit entitles it to rank among the treasures of the mediaeval world.'

'So far as any deduction can reasonably be made from the circumstances that go to form the history of the cup, it is fair to assume that it was made on French soil, and that it was made at the order of Duc de Berri, and not bought from a chance foreign goldsmith. To take the latter argument first; Charles V possessed a cup of gold weighing six mares, with the story of St. Agnes represented upon it, and he is stated to have had a special devotion to this saint, upon whose day he himself was born.'

The details of St. Agnes' story vary in the telling but all of them betray a similar drive. What follows is her story as it appears in Vetusta Monumenta MCMIV, written by Charles Hercules Read quoted above.

'The story of St. Agnes is a pretty legend. A rich and beautiful maiden in Rome at the end of the third century, she was sought in marriage by many suitors, but uniformly answered that her body was consecrated to a heavenly spouse, and she would have nothing to do with earthly marriage. The love or avarice of the aspirants turned into hate and a desire for revenge at the persistency of her refusals, and she was accused as a convert to Christianity. Neither threats nor blandishments, however, had any effect upon the resolution she had made and openly expressed. She was then shown the rack and other instruments of torture, and terrible fires into which she was to be cast alive. The result was the same; she remained obdurate, and professed the greatest readiness to undergo the torments of burning, which, some accounts say, had no effect upon her. As a final ordeal she was next consigned to a house of ill-fame, but, when there, those who could have rudely dealt with her were stricken with such awe as to form an efficient protection for the saint. One of these wealthy young Romans, named Procopius, more hardened than his fellows, would have offered violence to her, but on the instant was stricken with blindness and fell trembling to the ground. His terrified companions carried him to St. Agnes, who by her prayers restored him to health and gave him back his power of sight. Notwithstanding this miraculous intervention, the saint was ultimately beheaded by the order of the governor, who was urged to extreme measures by the virulence of her enemies. The chief scenes in the story are represented in the concise manner of mediaeval artist, those of her short life being seen on the cover, and the miracles performed at her tomb on the outside of the cup itself.'

The scenes on the cover are as follows: Each has a legend on a scroll explaining its meaning:

1. Procopius standing before the Saint offering her a casket of jewels.

2. The Saint standing before a small building, representing the house of ill-fame to which, on her refusal to marry, she has been consigned by the judge; Procopius lies apparently dead on the ground and the devil is about to carry him off.

3. St. Agnes has compassion upon Procopius and raises him to life, and dismisses him with an exhortation.

4. Sempronius and Aspasius, the two judges of the Saint.

5. The martyrdom of St. Agnes in the presence of Aspasius. The fire being ineffectual to kill her, though the executioner has to ward off the heat from himself with his hand; he then puts her to death by driving a spear into her neck, and she expires.

The remaining scenes are on the bowl:

6. The burial of the Saint. The body on a bier is covered with a pall having a plain cross upon it; a priest asperges the body and an acolyte stands by with a cross.

7. Scene at the tomb of St. Agnes, in which her sister, St. Emerentiana, is being stoned to death by three men.

8. The Saint with other martyrs appearing to her relations at her tomb.

9. The sick Princess Constantia lying on the tomb of St. Agnes, who appears to her.

10. The Princess Constantia, healed of her sickness, kneels at the feet of her father, the Emperor Constantine.

Within the cover beneath the finial is a circular disc in a raised setting enamelled in the same manner with a half-length figure of Our Lord in Glory, holding a chalice, and with other hand raised in benediction. A corresponding medallion in the bottom of the bowl has a beautifully designed subject of St. Agnes kneeling before an old man, her father or her judge. She hols a book in her hands.

On the lower part of the stem are the symbols of the Evangelists with their names on scrolls. The figure of the angel representing St. Matthew is of exceptional beauty, and being on a much larger scale than is possible in the scenes on the cup, the modelling of the features is full of character.

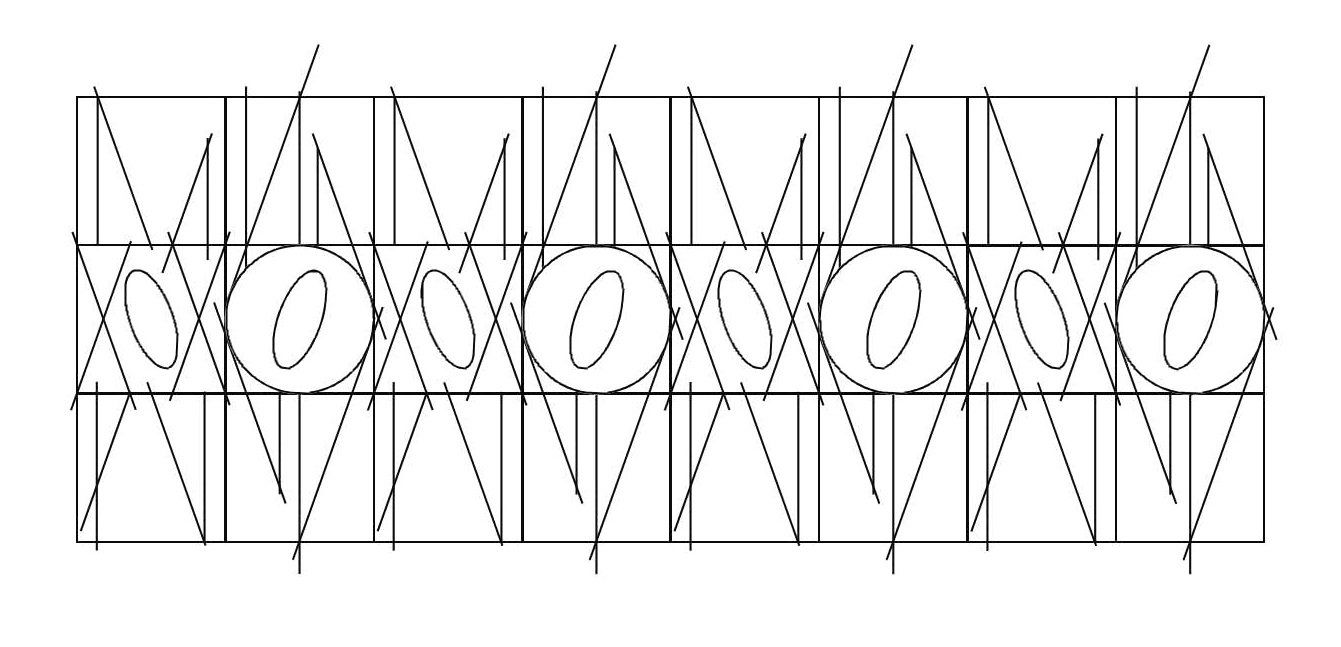

This is sort of odd but has stayed with me a long time... almost impossible to wear though

Adumbration

: Anodised silver, wood and copper brooch

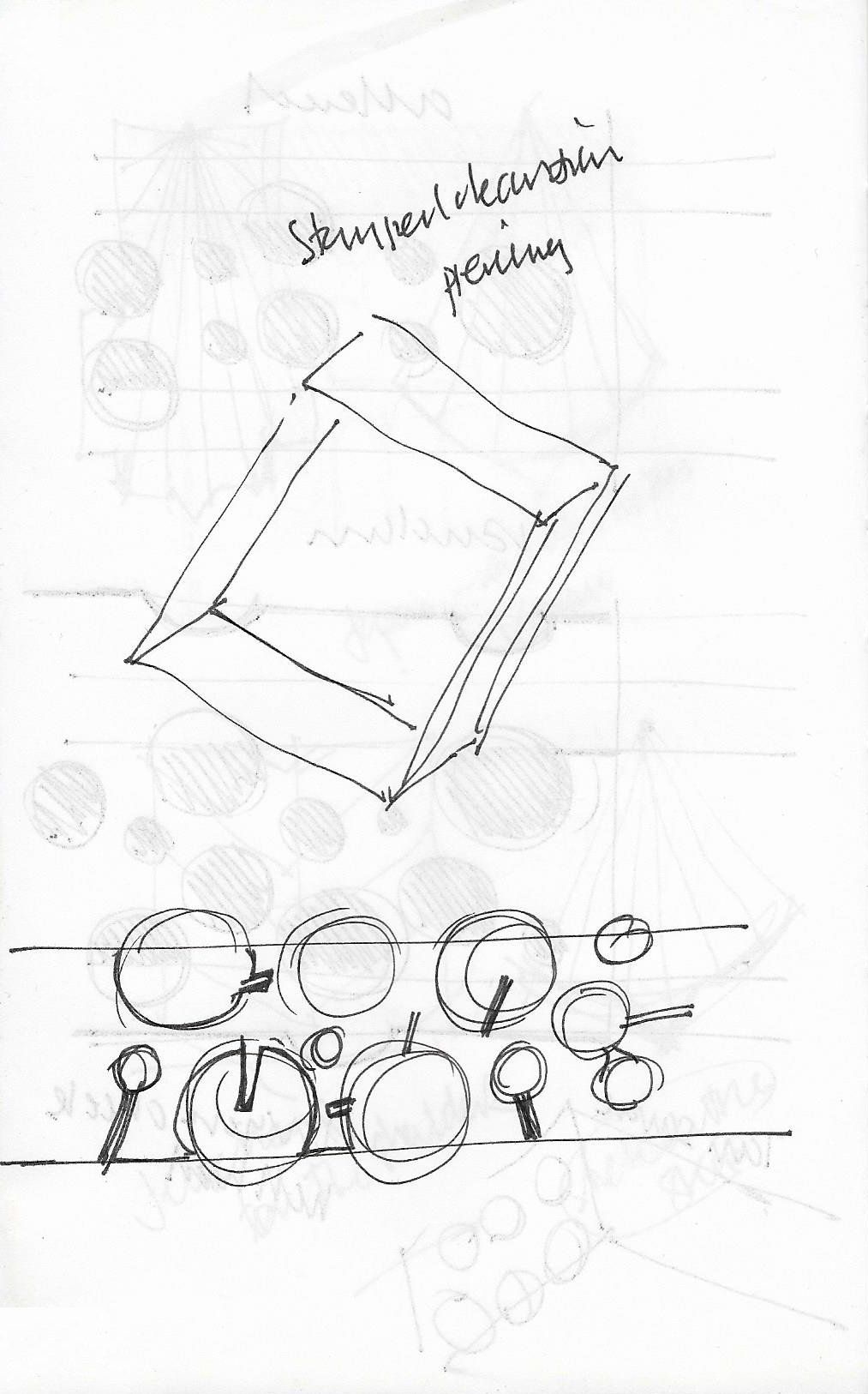

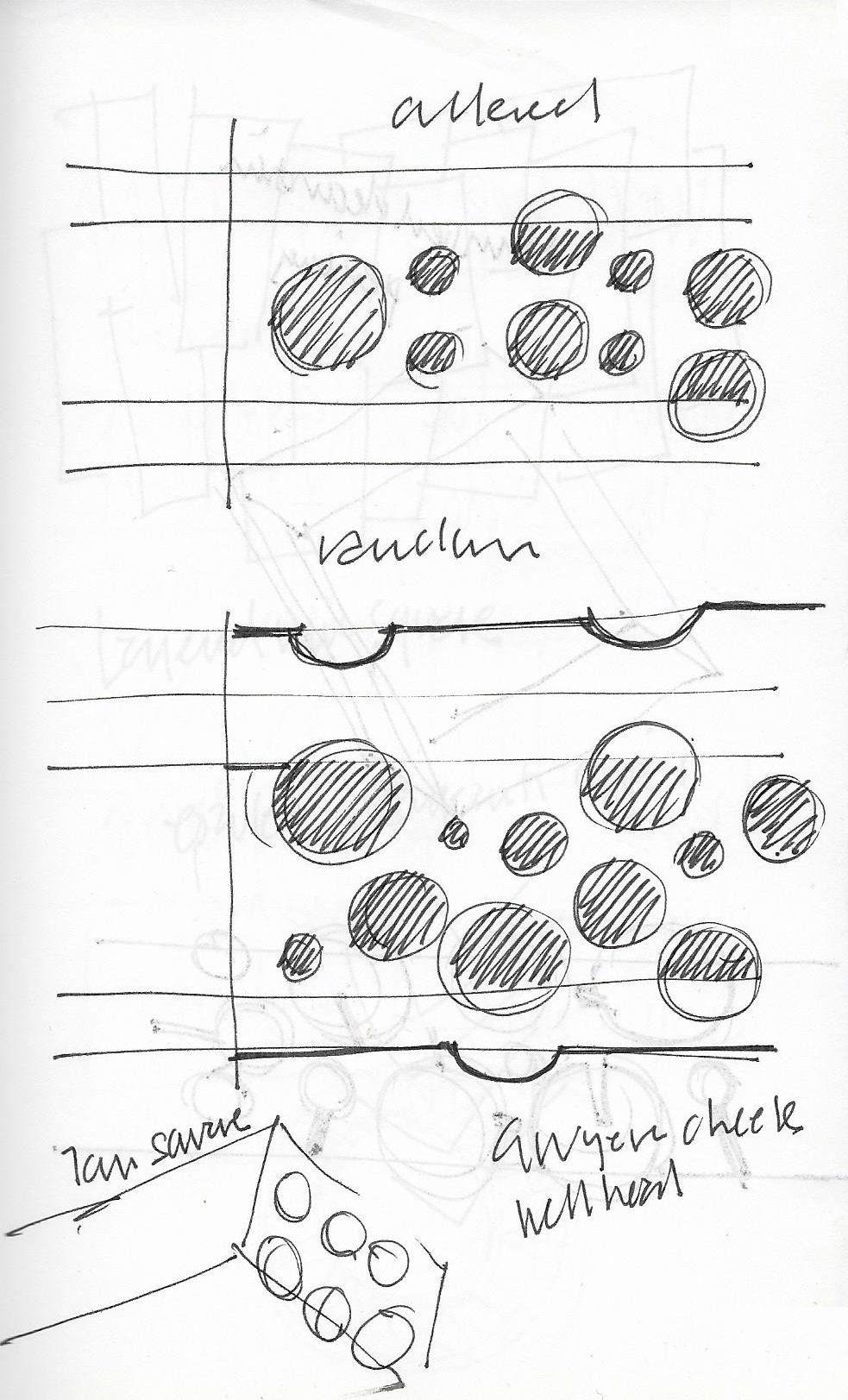

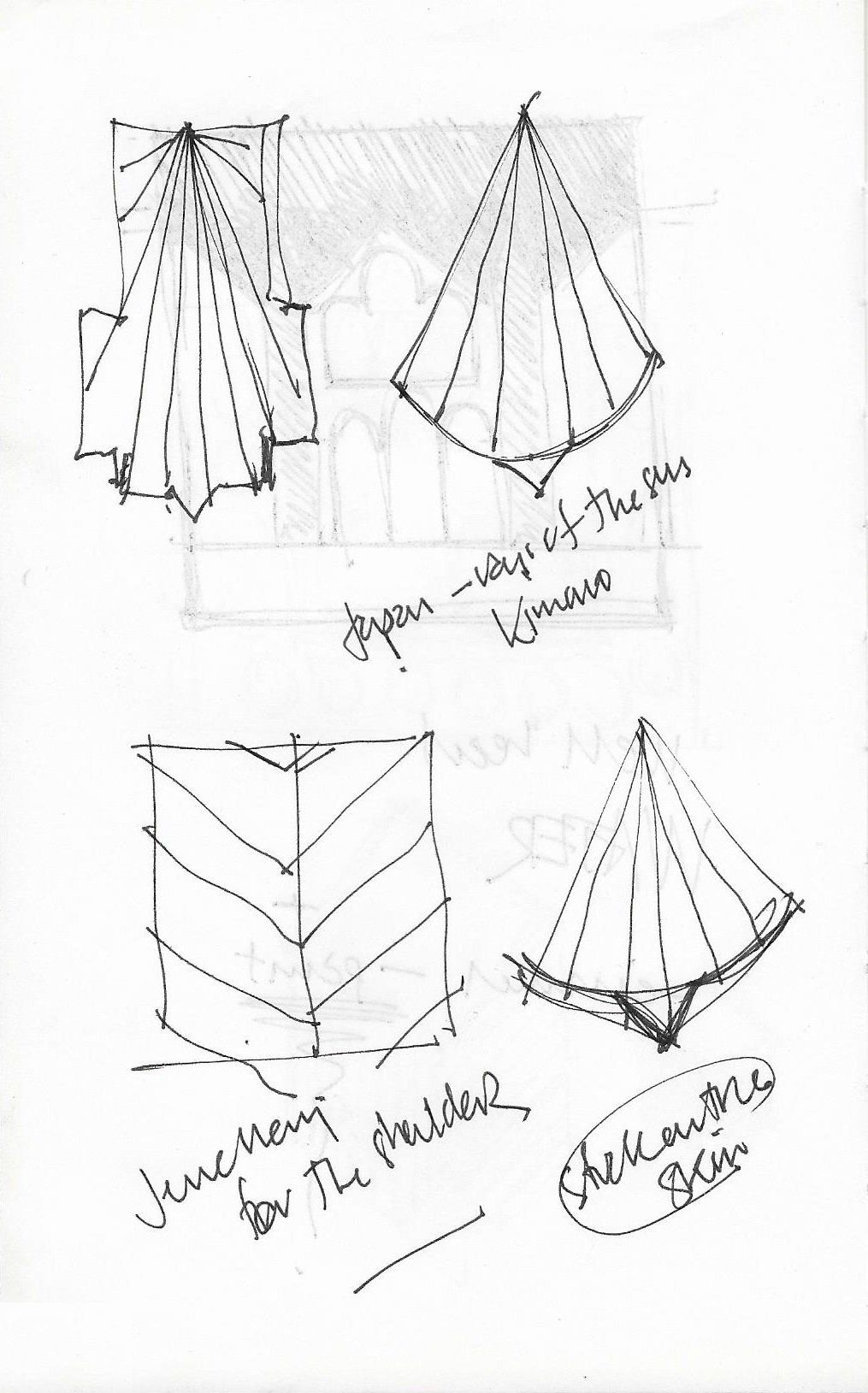

(2019) I finally, recently, got this one hallmarked. The whole thing has been a long time in the coming. It took a embarrassing amount time for me to become comfortable with the design. The original thought and subsequent sketches came quickly but they took an age to transfer into a usable plan (I exhibit a few of my attempts for your delectation below) - my eyes were square by the time I'd finished fighting with the 1:1 scale computer drawing. Getting to work, I made a couple of silver 'masters' for casting but the castings didn't quite turn out as I expected. After some thought (another month), I made the decision to bugger about with what I had rather than start again. I had it partially completed and then (apropos of my chosen vocation - how does one choose a vocation? Or does it choose us? I have no idea. We bandy the word about but I suspect most of us, even if we claim to have gathered one to ourselves, haven't a clue how we got here or what it means), moved house. The damn thing got lost in the move. You will know the sort of thing? Tucked it away somewhere safe and then couldn't remember where 'safe' was. It finally, recently, after I had given up all hope of ever seeing it again, turned up in the most unexpected place and finally I finished it. It's been the thick-end of decade in the making but bears a 2019 hallmark. Was it worth the effort? I'm happy to have finally beaten it into submission. I have another bracelet in mind at the moment (to be made entirely from silver tube). As and when I get round to it I hope it's an easier make than this one proved to be but I'm not holding my breath.